By now, the purpose of your assessment is clearly articulated. It’s time to put limits on what will be assessed. You must establish the specific geographic, temporal, and analytical scope for the work. This requires thoughtful consideration of stakeholders’ needs and concerns, a feel for the overall character of the watershed or river under consideration, and an initial identification of potential project management or implementation challenges.

Reflect on the Purpose

Your river health assessment’s purpose statement describes why the assessment should occur. Based on the purpose, the group of individuals and/or organizations planning for the assessment should brainstorm a list of primary questions and known problems they want the assessment to address (click here to see some pre-planning questions developed for Stream Management Plans). Group activities can be helpful here. For example, you might hang a large map of the watershed on a wall and ask stakeholders to place sticky notes or dots on areas of concern (e.g., “frequent algal blooms here”), key assets (“important fish spawning area here”), and major inputs to streams or rivers (“stormwater outfall here”). The notes placed on the map can be the basis for articulating questions about specific areas of the watershed or identifying (in a spatially explicit manner) problems that should be evaluated during the assessment.

Delineate Geographic Priorities

There is no optimal scale for an assessment. In fact, river health assessments may seek to characterize conditions across a wide variety of spatial scales, spanning a range from the channel scale (tens to hundreds of feet) to the reach scale (hundreds of yards to tens of miles) to the watershed scale (many square miles and multiple streams). In determining the “best” scale for your effort, consider the information collected in group activities like the one outlined above or through knowledge of the specific interests of your stakeholder group. This information may form the bounds of the locations or water bodies that are essential to include. It is also prudent to consider any relevant jurisdictional boundaries. For example, if the primary audience for your assessment is a City Council, it may make sense to limit your activities to the scope of City interests. Finally, anticipated budget availability may also constrain your geographic scope. Generally speaking, an effort that covers a greater number of stream miles will be more expensive. If you have limited funding for your assessment, making the geographic extent of your study area equivalently modest will help enable a reliable assessment of your highest priority resources. Where limited budget is available, but the demands of the assessment require a relatively large geographic scope, the assessment approach will need to be centered on low intensity, rapid methods (see section below).

Contemplate Analysis Intensity

The second part of scoping involves getting a handle on the assessment focus. Given limited time and resources, you will need to consider the most critical aspects of your river, those to which most energy should be directed, where you can leverage existing data and information, and where data gaps exist that will need to be filled. This step begins to span the gap between river health and stakeholder concerns. There is no need to address any of these topics in detail during scoping, but this contemplation and articulation will begin to refine expectations for the study and inform budget planning. This is somewhat technical, so you may wish to solicit assistance. Since this step is part of scoping for a future project, consultants or other experts may be willing to help on an informal basis.

Scoping analytical intensity comes down to deciding how much study time and resources should be devoted to assessing a unit length of stream or area of the watershed for each of the Drivers. In CoRHAF, the different Drivers can be evaluated at different levels of intensity to allow you to dial in assessment rigor according to circumstances in the watershed, stakeholder interests, likely budget, and geographic extent.

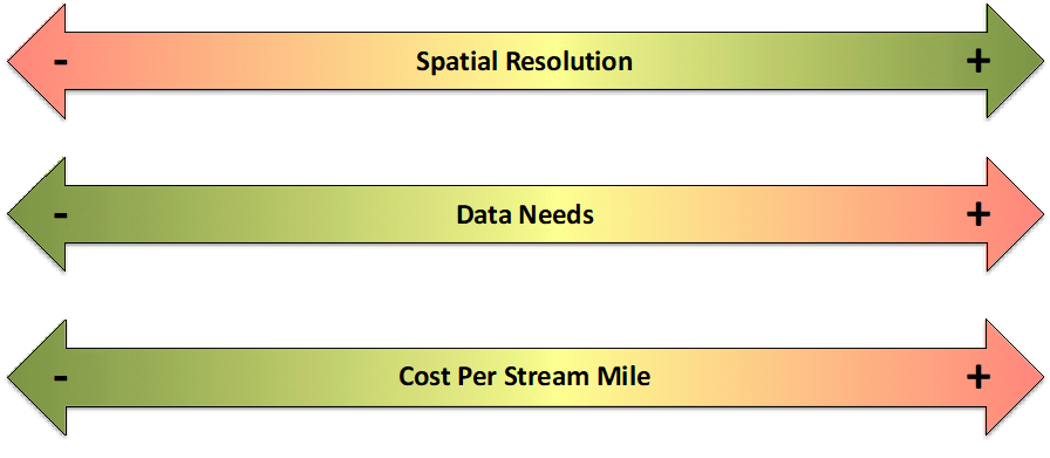

These decisions will also be influenced by the data resources available. Reviewing the CoRHAF Drivers in light of your known data sources and the factors that are important to the river(s) in your watershed will help you understand how involved an assessment is likely to be. Where river health conditions are not well understood and previous studies and relevant data are generally lacking, significant effort may be required to evaluate the condition of one or more Drivers that are important to stakeholders. Conversely, if current river health data is abundant and issues/areas of concern are already identified, the need for new data collection and analyses may be minimal. As a rule of thumb, assessing conditions at a high spatial resolution requires significant data collection and analysis and will be expensive on a unit length/area basis. If a project is constrained by limited budget and/or data, assessment activities will need to mainly rely on rapid methods, a coarser spatial resolution, and/or be limited to a modest geographic scope. In any case, the geographic scope of your assessment should weigh heavily in your consideration of which assessment intensities are best for the individual Drivers and/or Components in your assessment.

Assessment intensity refers to the amount of time and resources that are devoted to assessing a given unit length of river

To aid with planning and communication, CoRHAF stratifies assessment intensity into three levels: low-intensity remote assessments, moderate-intensity rapid assessments, and high-intensity focused assessments. Different assessment intensities can be used across Drivers and intensity may be varied among streams or reaches. For example, important Drivers or key locations can be assessed with high intensity approaches, whereas lower priority areas or Drivers can be evaluated at a lower intensity. Each assessment level is discussed below.

Level 1 – Remote Assessment

Remote assessments are the most efficient means for characterizing conditions across large areas with limited time and budget. Remote assessments are generally qualitative but may be quantitative in some cases. A qualitative remote assessment may rely on aerial imagery in web applications or a geographic information system (GIS) to gather visual impressions of local conditions and identify the variety, severity and distribution of stressors to river health. These impressions, in light of grading guidelines, then become the basis for the assignment of functional condition grades to Drivers or Components. A quantitative remote assessment could involve simple measures, such as the frequency of dams and diversions. Low-intensity remote assessments can incorporate sophisticated analyses such as appropriate floodplain modeling if they already exist. Typically these advanced analyses are used to make simple, quick measurements such as the percentage of remaining active floodplain.

Level 2 – Rapid Assessment

Rapid assessment occurs in the field. Like remote assessment, these assessment activities rely heavily on visual inspection and best professional judgement. They may or may not include data collection. If they do, those data will be collected using rapid methods, without technical apparatus such as vegetation plots or survey equipment, other than a handheld GPS or similar devices. Rapid assessment may produce quantitative data, such as a visual estimation of shrub coverage or percent embeddedness of the bed, but, again, those data are derived through broad estimations rather than detailed systematic sampling. Walking or floating a river reach and recording observations of substrate embeddedness, coarse bed structure, and other characteristics of river form is a common form of rapid assessment. Questionnaires that cue the observer to certain characteristics of the system can be helpful to promote consistency in rapid assessment and ensure that grading rationales are documented.

Level 3 – Focused Assessment

Focused assessments generally produce quantitative outputs. These methods assess conditions at a single point or across a relatively small floodplain area or stream reach. Depending on the assessment goals and geographic extent, a large number of distinct sampling locations could be needed to adequately characterize the study area. Focused assessment techniques are the most expensive and data intensive to implement, and thus tend to be used to characterize relatively small geographic areas. Examples of focused assessments include characterization of riparian community structure by way of recording vegetation species composition along fixed transects or within plots, development of 1-dimensional or 2-dimensional habitat suitability models, sampling macroinvertebrate populations to calculate multi-metric indices (MMIs), or collection of streambed substrate data to characterize bed composition and model bedload transport. The characteristics or processes revealed through application of these methods at the local scale may or may not represent conditions across larger areas, so keep that in mind during initial scoping and later as the assessment approach is developed in detail.

Potential Assessment Intensities for Various Drivers

Flow Regime For a coarse analysis of hydrology, understanding of the general patterns and large-scale alterations or modifications to a river’s flow regime may be all that is needed. More detailed assessments may include detailed investigations of flow alteration including hydrological simulation modeling, statistical characterization of regime behavior, and/or trends analysis.

Sediment Regime High-level evaluation of sediment regime may involve rapid assessment techniques to characterize patterns of local and watershed-wide impacts to sediment supply, erosion, deposition, and transport such as clear-cut logging operations or widespread clearing of bankside woody vegetation. Detailed investigations may focus on site-specific relationships between channel hydraulics and lateral channel migration rates, the frequency and duration of significant streambed mobilization, relationships between sediment regime and spawning habitat quality, or modeling of hillslope processes in priority areas.

Water Quality Coarse investigation may rely on general examination of existing datasets, reports, and agency assessments from CDPHE or EPA. For streams lacking existing water quality data, stressors (e.g., point and non-point sources of pollution) can be identified and their effects on water quality inferred and subjectively rated. Detailed technical investigations may include new sample collection, statistical analyses of historical trends, or modeled interpolation of conditions between sample points

Wood Regime Coarse- or moderate-scale analysis may involve rapid field assessments and floating or ‘windshield’ surveys. Detailed investigations may involve modeling of wood recruitment, storage, and transport. Additional work may also explore the nexus between wood regime and fishery habitat condition.

Riparian Habitat Remote riparian assessments may rely primarily on aerial photo interpretation of land cover and land uses within the riparian zone and the amount of remaining riparian habitat. Rapid field assessments relying on float or walking surveys where access is possible may augment or field verify remote sensing data. Focused investigations might create high resolution imagery using drone-based photography and image analysis, or permanent sampling points to quantitatively benchmark riparian condition.

Channel Dynamics Channel dynamics might be assessed remotely by considering factors like watershed-scale stressors such as burn-scars or reservoirs that alter sources and sinks of sediment, alterations of streamflow, and reach-scale stressors like bank armor, woody vegetation clearing, channel spanning structures, and encroachment, and then interpreting how the interplay between those factors likely degrades processes including aggradation, incision, or the ability of the river to move across its floodplain. Detailed evaluations may include quantitative estimates of bed sediment transport, historical mapping and/or modeling of channel migration rates, or development of quantitative regional relationships between rates of channel change and other environmental variables (e.g., riparian vegetation extent, metrics of hydrological regime behavior, etc.).

Aquatic Habitat Coarse investigations may rely on rapid field assessments, aerial photography and other remotely sensed data, and reviews of existing habitat studies. Detailed investigations may utilize channel surveys and hydraulic modelling that relates different streamflow conditions to micro- or meso-habitat quality and availability for a species and/or life stage of interest. Alternatively, detailed assessments may include techniques like snorkel surveys of organism habitat use, quantification of embeddedness, habitat mapping, or bioenergetic habitat suitability modeling

Aquatic Food Webs Coarse assessments may rely on basic first-principals in freshwater ecology, rapid field surveys, and existing reports from CPW or other agencies. Detailed investigations may include macroinvertebrate sampling or targeted fish shocking. Alternative techniques may attempt to quantify energy, nutrient, or carbon inputs from riparian zones and/or upstream areas or may measure processes like whole stream metabolism.

Consider Project Timelines

The temporal scope of your assessment includes the overall project duration and timing of project milestones. The timeline is intrinsically linked to the budget, the assessment priorities, and obligations or deadlines associated with grant funding sources. Seasonality is also a critical consideration! Many types of information can only be collected at certain times of year. Meshing this natural constraint with funding awards can be challenging. Creating a temporal scope for your project begins by listing all known project timeline constraints and stakeholder preferences for the timing of interim project deliverables. Use external deadlines, such as grant reporting requirements, governmental decision-making schedules or seasonal limitations to impose firm constraints on overall project duration. Then work backwards to define timelines for any other project milestones or interim project deliverables. It is important to consider your expectations for assessment intensity while building a project timeline. If you expect your river health assessment to cover a large region and to utilize multiple focused quantitative assessments, you will need to allot more time than an effort that is more geographically constrained or reliant on remote assessments.

Scope Your Project

Selection of the ideal geographic scope and assessment intensity for your river health assessment can be an iterative process that attempts to grapple with tension between the desire to assess conditions across large areas at a high level of detail and the reality of limited time and budgets. Arriving at a final scope may require evaluation of multiple distinct and plausible assessment scenarios that reflect different geographic, analytical, and temporal characteristics (e.g., “Scenario A is a comprehensive, multi-year baseline study but is expensive; Scenario B is a lower-cost, single-season study focused on a priority sub-watershed”). Project planners can evaluate each scenario’s cost, complexity, and timeline implications against a set of agreed-upon criteria. These criteria might include:

Relevance: How well does this scenario respond to project’s purpose statement?

Comprehensiveness: Does it include the primary sources of impact and key geographic areas?

Feasibility: Is this scenario realistically achievable within our likely budget and timeline?

Actionability: Will the results from this scope lead directly to tangible management actions or policy decisions?

Data Availability: Does the scenario effectively leverage existing data or does it rely on extensive new data collection?

The outcome of such an evaluation may be the adoption of a single scenario as the preferred project scope. Equally plausible is the combination of desirable elements from different scenarios. For example, the group might choose the geographic scope of Scenario B but incorporate the more detailed analytical intensity for a specific Driver or Component from Scenario A, while adjusting the timeline to seek additional funding sources to support an expanded budget. This iterative refinement can help you identify a scope that is responsive to the stated purpose, reflective of budget realities, and is highly likely to produce outputs for the stakeholders and focus audience that are both timely and relevant.