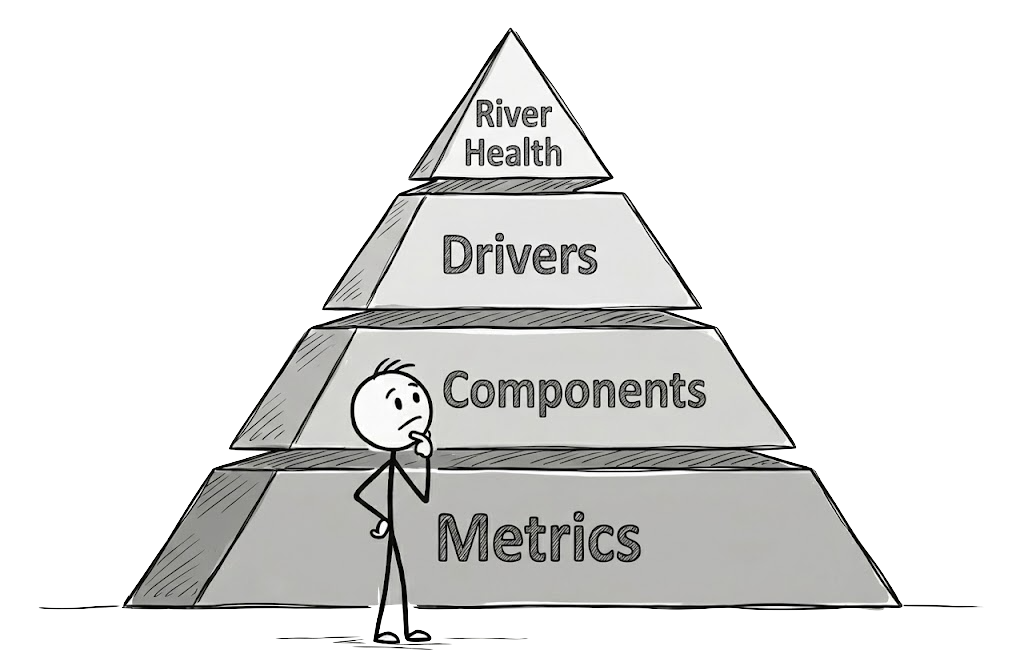

Core Structure

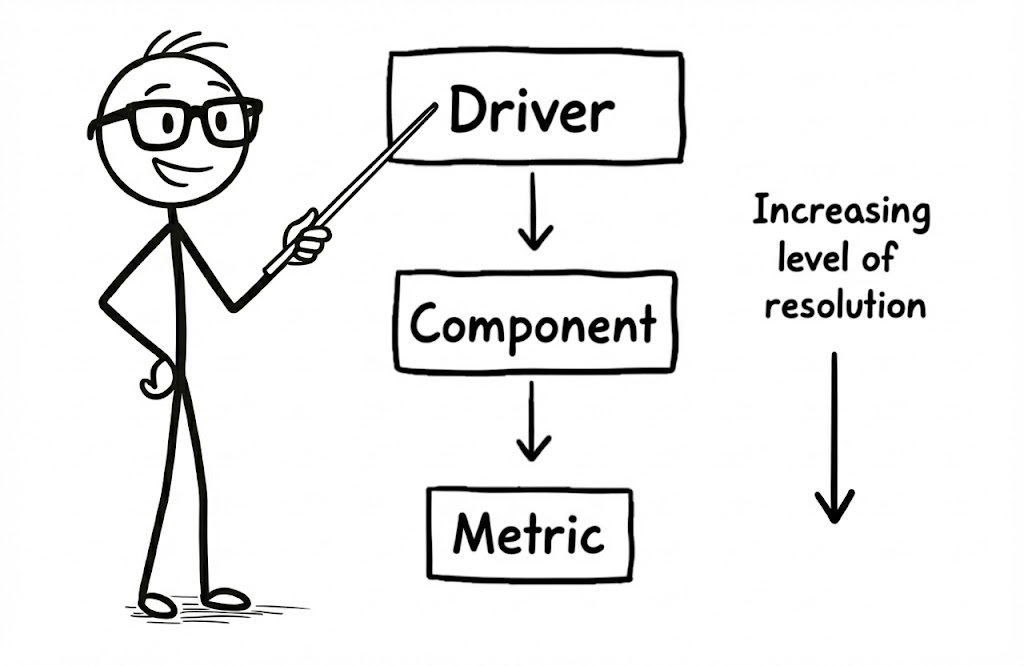

Riverine ecosystems are characterized by dynamic interactions between flowing water, sediment, wood, nutrients, and biota throughout a stream network, within a channel, and across adjacent floodplains. River health, often conceptualized as ecological integrity, represents the ability of these systems to maintain their characteristic structure, composition, and function within the natural range of variation. At its core, CoRHAF is an organizational framework that decomposes the abstraction of river health into a set of hierarchically nested concepts. Each step down in the hierarchy corresponds to an increasing level of resolution in the definition and assessment of river health.

Organization of River Health Concepts

CoRHAF relies on a conceptual structure that organizes river health around key Drivers of river health. A river’s Flow Regime is an example Driver. Drivers are conceptual representations of the numerous physical and biological aspects of aquatic ecosystem structure and function that govern river health. CoRHAF decomposes Drivers into constituent Components. For example, Peak Flow is a Component of the Flow Regime Driver. Components can be assessed qualitatively or quantitatively, depending on the needs of a particular health assessment. In cases where quantitative assessment of Components is desired, those Components are further decomposed into Metrics. The average annual 3-day peak flow, for example, is a Metric that can be quantified to represent the Peak Flow Component. Quantitative methods are applied to evaluate Metrics. In the case of the average annual 3-day peak flow, statistical characterization of streamflow time series data collected at a stream gauge to generated quantitative outputs.

CoRHAF presents a set of default Drivers and Components that may be useful in many river health assessment contexts. However, those Drivers and Components do NOT comprise an exclusive or compulsory set of the characteristics and functions that mediate the condition of streams and rivers. They are intended to be a helpful foundation and a means of facilitating consistency among the many health assessments completed across the state. Thoughtful evaluation of local conditions and the goals and objectives of a given assessment effort should help practitioners and stakeholder groups assess whether addition, modification, or removal of Drivers and Components is necessary. The systematic evaluation and selection of Drivers and Components is a critical step on the path toward successful implementation of the CoRHAF.

Drivers

Drivers sit at the top of the hierarchy. These are broad categories of river ecosystem condition and function that represent whole scientific diciplines. The set of default Drivers included in CoRHAF is intended to encompass the fundamental aspects of most river systems found in Colorado. Drivers exert strong influence on river conditions. In cases where a Driver exists in a highly-functional state, the corresponding effect on river health is positive. Conversely, where a Driver exists in a degraded state, the corresponding effect on river health is negative. In this way, the functional state of these abstractions “drive” river health outcomes. Degradation of one Driver usually impacts the functioning of other Drivers. The default structure of CoRHAF includes nine Drivers:

The inclusion of these Drivers in CoRHAF does not suggest they comprise an exclusive set of characteristics, processes, and functions that mediate the condition of streams and rivers. Addition, modification, or removal of one or more Drivers may be necessary in any given assessment. Neither are these Drivers intended to be entirely distinct and independent from one another. In many cases, significant overlap, synergistic effects, or feedbacks may exist between one Driver and another. Recognizing and understanding these interactions is key to thoughtful health assessment implementation and results communication.

Components

Drivers are abstract and unmeasurable by their nature. In most cases, decomposing Drivers into multiple constituent parts can facilitate assessment of river conditions. These constituent parts are termed Components in CoRHAF. Components are used to highlight the most important aspects of each Driver.

Typically, each Driver is decomposed into two to four Components. Some cases that require a particularly detailed evaluation of Driver condition may necessitate inclusion numerous additional Components. CoRHAF makes no recommendation for the optimal number of Components. Rather, tailoring the selected Components to match the specific needs of the project is left to practitioners and Technical Teams. A few examples are listed below, but many more can be considered when designing an assessment.

Peak Flow

Peak flows are generated by processes that deliver large volumes of water to the channel network rapidly. Common mechanisms include intense or prolonged rainfall, rapid snowmelt, or a combination thereof. In Colorado, the dominant mechanism for peak flows in many river systems is spring snowmelt, resulting in a predictable seasonal pulse. However, intense summer thunderstorms can generate flash floods, especially in smaller or arid catchments. Rain-on-snow events can cause significant winter or spring flooding in some areas. The specific characteristics of peak flows are modulated by catchment properties like size, shape, geology, topography, soil type, and vegetation cover, which influence runoff generation and routing. Key characteristics of peak flow include its magnitude, duration, and seasonal timing.Peak flows are the primary agents of geomorphological work, responsible for mobilizing and transporting the bulk of sediment and large wood, actively shaping channel morphology (width, depth, pattern), scouring pools, building bars and riffles, and driving lateral channel migration. By exceeding channel capacity, peak flows facilitate lateral connectivity with floodplains and riparian zones. This connection is vital for exchanging water, nutrients, organic matter, and organisms between the channel and floodplain, recharging riparian aquifers, scouring floodplain surfaces, and depositing sediments. Floodplain inundation creates temporary habitats crucial for the life cycles of many fish and other aquatic organisms. Peak flows also create and maintain habitat diversity within the channel itself, for example, by flushing fine sediments from gravels used for spawning by several fish species, or by scouring deep pools that serve as refugia. Furthermore, floods act as ecological disturbances, preventing the encroachment of upland vegetation into the channel, creating bare ground necessary for the establishment of pioneer riparian species like cottonwood and willow, providing dispersal mechanisms for seeds, and resetting algal and invertebrate communities. The timing and magnitude of peak flows also serve as critical environmental cues triggering life history events such as migration and spawning for many aquatic and riparian species.

Human activities can profoundly alter peak flows. The construction of reservoirs is arguably the most significant impact. Reservoirs typically capture floodwaters, drastically reducing the magnitude, frequency, and duration of peak flows on downstream segments and often altering their seasonal timing. This impact can produce numerous ecological consequences, including channel narrowing and incision, hydrological disconnection from floodplains, loss of dynamic bar and island features, reduced rates of lateral channel migration, and a decline of species dependent on flood pulses or specific flood-created habitats. Changes in land cover produced by urbanization or large wildfires can reduce infiltration rates, leading to more rapid runoff and increased magnitude of flood events. Large scale shifts in climate can influence the timing and magnitude of peak flows by shifting the timing of snowmelt onset and driving large and more sporadic monsoonal rainfall events.

Base Flow

Baseflow is the portion of the hydrograph that persists flow during the late summer and fall dry periods and through the winter months. While groundwater is the main source of baseflows in the river in most settings, contributions can also come from shallow subsurface flow or, in regulated systems, from augmented releases from reservoirs or groundwater return flows from irrigation. Key characteristics of baseflow include its magnitude, duration, and seasonal timing.Baseflows help maintain wetted habitat and provide hydraulic refuge for aquatic organisms during the late summer, fall and winter months. Sustained baseflow is also crucial for maintaining floodplain aquifers and supporting riparian vegetation. Robust baseflows can contribute to high water quality by diluting pollutants entering the stream and moderating summer water temperatures. Baseflow magnitude and duration also directly define the availability and connectivity of aquatic habitat for many aquatic organisms. Extremely low flows can reduce the total area of different habitat types (e.g. pools and riffles) and limit organism passage through particular reaches, isolating populations and making them more vulnerable to stressors and environmental perturbations.

Human activities frequently impact baseflows, often leading to reductions that stress aquatic ecosystems. Extensive groundwater pumping for agricultural irrigation or municipal supply can lower water tables, diminishing the hydraulic gradient that drives groundwater discharge into streams. Direct surface water diversions that support agriculture, industry and municipalities generally reduce baseflows in a stream. Dams and reservoirs have complex effects: storage reservoirs may decrease baseflows downstream, or they may artificially increase and stabilize baseflows through operational releases for hydropower, irrigation, or downstream water supply. These regulated baseflows, however, often lack natural seasonal variability and exhibit altered temperature profiles that interfere with life stage cues and growth rates of aquatic organisms. Urbanization can reduce groundwater recharge and lower baseflows. Widespread deforestation can alter evapotranspiration and infiltration rates, potentially increasing or decreasing groundwater levels. Agricultural return flows (surface water and groundwater) can sometimes augment baseflows, but this water may be of poor quality, carrying excess nutrients or salts. Climate change is projected to severely impact baseflows. Reduced snowpack accumulation, earlier snowmelt, and increased summer evapotranspiration may conspire to significantly lower summer and fall streamflows. More frequent and severe droughts might further exacerbate baseflow depletion.

Rate of Change

Rate of change describes the “flashiness” of a river’s flows across different time scales (e.g., seasonal, weekly, daily). Natural rates of change are governed by factors influencing how quickly water reaches and moves through the channel network. These include the intensity and duration of rainfall or snowmelt, the size, shape, and slope of the catchment, the density of the drainage network, soil infiltration rates and storage capacity, and the amount of storage within the channel and floodplain. Smaller headwater streams often exhibit faster rates of change across multiple time scales than larger rivers.The rate at which flows change has significant ecological implications. At the seasonal scale, both rising and falling limbs of a snowmelt hydrograph can act as important cues for fish behavior, such as initiating upstream migration or triggering spawning activity. The rate of flow recession is particularly critical. A gradual recession allows organisms time to move out of temporarily inundated areas (like floodplains or side channels) back into the main channel, reducing the risk of stranding. Gradual hydrograph recession rates in are also important for the establishment of certain riparian vegetation species, like cottonwoods, which require moist, bare sediment surfaces for germination and early growth. Conversely, extremely rapid changes in flow, whether increasing or decreasing, can impose physiological stress on aquatic organisms adapted to more stable conditions.

Human activities have dramatically altered natural rates of flow change in many rivers. Dams operated for hydropower generation often engage in “hydropeaking,” characterized by very rapid increases and decreases in discharge over hourly or daily cycles to meet electricity demand. These unnatural, rapid fluctuations create highly unstable downstream environments, disrupting sediment transport, causing habitat scouring or dewatering, increasing the risk of organism stranding, and interfering with life cycle cues. Urbanization, with its increase in impervious surfaces and engineered drainage systems (storm sewers), accelerates the delivery of rainfall runoff to streams, resulting in much faster rates of rise and higher peak flows for smaller storm events—increased flashiness. Channelization and levee construction reduce the natural storage capacity of the channel and floodplain, causing floodwaters to move downstream more quickly and potentially increasing rates of rise and fall. Climate change may also influence rates of change; projections of more intense precipitation events could lead to increased flashiness in some regions, while shifts towards earlier and potentially more rapid snowmelt could alter the character of seasonal hydrograph patterns.

Total Volume

Total flow volume accounts for the cumulative amount of water passing a specific point in the river over a defined period, such as a season or year. It integrates the magnitude and duration of all flow events, from baseflows to floods, within that period. The total volume of river flow is primarily governed by the water balance of its contributing watershed: precipitation inputs (rain and snow) minus water losses through evapotranspiration (evaporation from surfaces and transpiration by plants) and deep percolation into groundwater systems not connected to the stream. Watershed characteristics such as size, geology, soil types, topography, and vegetation cover significantly influence these processes and thus the total runoff volume. Total flow volume is a coarse component that reflects the river’s ability to do geomorphological work , its ability to assimilate pollutants, and its ability to support diverse aquatic and riparian habitats. Total volume, particularly the magnitude of higher flows integrated over time, plays an important role in streambank erosion and sediment transport–scaling processes that influence the physical dimensions of the channel.Human activities, particularly those involving water management and land use, can significantly alter total flow volumes. Reservoirs, while primarily altering flow timing, can also reduce downstream volume through increased evaporation from the large surface area of the impoundment. Consumptive surface water diversions and groundwater withdrawals for agriculture, municipal, and industrial purposes, directly subtract water from the river system, reducing the total volume flowing downstream. Transmountain diversions, common in Colorado for supplying water to Front Range cities and agricultural areas, physically remove water from one watershed and add it to another, decreasing volume in the source basin and increasing volume in the receiving basin. Urbanization typically increases total runoff volume by reducing infiltration and evapotranspiration. Large-scale changes in forest cover due to resource extraction or wildfire an modify watershed evapotranspiration rates and potentially increase water yield over the short term. Climate change projections generally indicate a trend towards reduced total annual flow volumes in many Colorado streams, driven primarily by increased temperatures and higher evapotranspiration rates in source watersheds.

Watershed Sediment Supply

Watershed sediment supply accounts for the delivery of sediment from hillslopes to the river. This supply tends to be greatest in headwaters and canyons where hillslope processes dominate the steep landscape. In healthy watershed areas, the rate at which sediment is supplied to the river is matched by the river’s capacity to transport that sediment; although acute inputs from debris flows and other mass wasting events periodically cause temporary imbalances. The sediment supply from the watershed is essential to proper river functioning.Generally, land cover or land use changes result in increased hillslope erosion and elevated watershed sediment supply to channels. Forest clearing, wildfire, road building, agriculture and a host of other activities increase watershed sediment supply. Wildfire has the greatest impact on rates and volumes. Excess erosion and supply from the watershed cause a host of problems for river health. Channels may experience rapid aggredation and avulsion and streambeds may become clogged with fine sediments. Dams and reservoirs can disrupt the supply of sediments to downstream channels. Where sediment delivery is limited, rivers may experience armoring of bed sediments and a corresponding degradation in habitat quality for fish and macroinvertebrates.

Localized Sediment Supply

Bank erosion and mobilization of sediments from the streambed provide rivers with a localized sediment supply. The role of localized sediment supply in maintaining river health reflects the watershed sediment supply. In many settings, the ideal localized supply is balanced by the river’s ability to transport that supply. Natural sediment supply through channel erosion can vary greatly depending on a variety of interrelated factors including position in the watershed, channel gradient, channel sinuosity, and dominant bed and bank material.Depending on the context, localizezed sediment supply from bank erosion may be viewed positively or negatively. Bank erosion is a natural process that occurs as rivers adjust their planform, profile, or channel dimension in response to changes in the sediment or flow regime, or during large flood events. However, numerous human activities can alter localized sediment supply. Rates of streambank erosion may be elevated by the clearing of near-channel vegetation, which removes the stabilizing effect of plant roots. Increases in the ‘flashiness’ of the stream hydrology in response to urbanization or wildfire can also increase rates of streambank erosion. Streambank armor (e.g., rip-rap) is often used to arrest localized bank erosion. Reductions in localized sediment supply due to bank armor can limit the progressive development of downstream point bars, areas critical to the recruitment of new riparian vegetation. Channel straightening and bank armoring can lead to excess hydraulic energy that winnows fines from the streambed and leads to bed armoring. Armoring of the streambed reduces habitat quality for macroinvertebrates and makes riffles less suitable for fish spawning.

Sediment Continuity and Transport

Continuity and Transport represent the movement of sediment supplied to the river. Ideally, sediment moves through the river system in a characteristic fashion, including relatively rapid movement through steep and narrow reaches, and much slower movement through wide depositional reaches. Depositional reaches may aggrade with surplus sediment and exhibit elevated rates of lateral channel movement or avulsion.Human activities that alter sediment continuity and transport can accelerate or decelerate the processes responsible for maintaining dynamic channel forms and high quality habitats. Downstream sediment movement can be disrupted by channel-spanning structures (e.g., low-head dams or water diversions) or in-line reservoirs. Water withdrawals and other diruptions to the hydrologic regime can limit the stream’s ability to mobilize sediment and transport sediment.

Wood Recruitment

Wood recruitment encompasses all processes by which wood enters the river corridor from adjacent or upstream sources. Natural recruitment occurs through various mechanisms operating at different temporal and spatial scales. Regular input results from the mortality of individual trees within the riparian zone that fall directly into or near the channel. The rate of input varies with forest type, age structure, and health. Episodic inputs of larger wood volumes can be driven by rapid bank erosion during floods that undercuts and topples riparian trees. Landslides, debris flows, or avalanches originating on adjacent hillslopes can also transport large quantities of wood to the channel. Large-scale disturbances like major floods or stand-replacing wildfires can cause widespread tree mortality and deliver substantial pulses of wood to river networks. Beavers contribute significantly to wood recruitment in many small streams through their dam-building and tree-felling activities. The relative importance of these different recruitment processes varies depending on the geomorphic setting (e.g., confined canyon vs. wide floodplain), position within the watershed, and the natural disturbance regime.Human activities can drastically alter wood recruitment patterns. Logging, urbanization, and other land clearing activities that directly remove vegetation from riparian zones can produce long-term reductions in wood recruitment rates. Conversion of riparian forests to agriculture or urban development completely and permanently eliminates local wood sources. Road construction near streams can prevent trees from falling into the channel and can intercept wood delivered by hillslope processes. Altered fire regimes due to fire suppression can lead to changes in forest structure and potentially increase the risk of severe wildfires that cause massive, pulsed recruitment events. Dam construction eliminates recruitment within the inundated reservoir footprint and traps wood transported from upstream, preventing its delivery to downstream reaches.

Transport and Storage

Wood storage refers to the quantity, spatial arrangement, and persistence (residence time) of wood pieces retained within a river reach. the wood regime encompasses both individual logs and complex accumulations known as log jams. Wood transport describes the downstream and lateral movement of wood pieces within the river corridor. Mobilization and transport occur primarily during high-flow events when the hydraulic forces exerted by the water overcome the resisting forces of the wood pieces. Wood can be transported in several ways: floating freely, partially submerged, or by dragging, rolling, and sliding along the channel bed or banks. Transport in Colorado streams and rivers generally involves the movement of individual, dispersed pieces of wood. In very steep mountain channels, debris flows can transport enormous volumes of wood and sediment rapidly downstream. Wood becomes stored when the forces exerted by the flow are insufficient to move it, or when it becomes lodged against or within physical features of the river corridor. Common storage locations include the channel bed, banks, mid-channel bars, islands, and floodplain surfaces. The distance wood travels depends on a complex interplay of factors, including the size and buoyancy of the wood piece relative to the channel dimensions (width and depth), the magnitude and duration of the transporting flow, and the frequency and effectiveness of trapping features along the transport path. Large logs in small streams may be immobile or move only short distances, whereas smaller pieces in large rivers might travel further before being stored. Wood transport is often intermittent; pieces may be mobilized during a flood, travel some distance, become stored again, and then mobilize in a subsequent flood. The storage capacity of a reach is strongly controlled by channel width relative to wood length, channel complexity (sinuosity, braiding, presence of side channels), confinement, and the abundance of trapping features like boulders, bedrock outcrops, channel bends, constrictions, existing jams, and robust riparian vegetation. Generally, wider, unconfined, and more complex river corridors with abundant obstructions tend to have higher wood storage capacity compared to narrow, straight, or simplified channels.Stored wood is the functionally active component of the wood regime, directly mediating channel dynamics and aquatic habitat quality. Stored wood pieces create scour pools, backwaters, eddies, and areas of reduced velocity that serve as critical refugia for aquatic organisms. These hydraulic effects promote the trapping and sorting of sediment and organic matter, influencing bed morphology and substrate composition. Log jams, in particular, can force pool formation, stabilize banks, initiate bar or island development, and even trigger channel avulsions. The physical structure of wood provides some organisms with direct cover from predators and attachment sites for invertebrates and algae.

Human activities can dramatically influence wood transport and storage. Channelization, straightening, and levee construction simplify channel morphology, remove natural trapping features like bends and side channels, and increase flow efficiency, thereby reducing the river’s capacity to store wood and promoting its rapid downstream transport. Alterations to the flow regime, particularly the reduction of peak flows, decrease the hydraulic energy needed to mobilize and rearrange stored wood. Long-term reductions in wood recruitment due to logging or riparian clearing inevitably result in diminished wood storage in downstream reaches, as existing wood decays or is transported away without adequate replacement. Dams and reservoirs trap wood transported from upstream, preventing its delivery to downstream reaches.

Nutrients

Nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) are essential nutrients, required for the growth of primary producers (e.g., algae and aquatic plants) which form the base of most aquatic food webs. These nutrients occur naturally in various dissolved inorganic forms (e.g., nitrate [N.-], ammonium [N.+], phosphate [P.-]) and organic forms. Phosphorus tends to bind strongly to soil particles and is primarily transported via erosion, while nitrogen is more water-soluble and readily moves through surface runoff and infiltrated groundwater. Ambient concentrations in the water column are influenced by watershed geology, soils, vegetation, and atmospheric inputs. While essential in limited amounts, excessive inputs of N and P from human activities can lead to eutrophication.Major anthropogenic sources of nutrients to Colorado’s waterways include agricultural activities, wastewater treatment, and urban runoff. Agriculture is often the dominant nutrient source in many watersheds. Runoff from agricultural lands can carry excess nutrients from chemical fertilizers and animal manure. Wastewater effluent from municipal sewage treatment plants represents a significant point source of both N and P, although advanced treatment can reduce these loads. Failing septic systems in rural areas may also contribute nutrients via groundwater. Stormwater runoff from urban and suburban landscapes carries nutrients from lawn fertilizers, pet waste, detergents, and other sources. These loads can be quickly transported in high-concentrations to streams and rivers during precipitation events.

The ecological consequences of eutrophication can be severe. Eutrophication fundamentally alters aquatic community structure and food web dynamics, often favoring tolerant species over sensitive ones. Increased nutrient availability stimulates excessive growth of algea and rooted plants. This increased primary production can initially seem beneficial, but the subsequent decomposition of large amounts of dead plant biomass consumes large quantities of dissolved oxygen (DO) from the water column, particularly near the sediment surface. This can lead to low DO levels that are problematic for most benthic macroinvertebrates and fish. Certain types of algae, particularly cyanobacteria (blue-green algae), can produce potent toxins during blooms in lakes and reservoirs, which are harmful or lethal to fish, wildlife, domestic animals, and humans.

Metals

Numerous metallic elements are present in the water column. Common metals of concern in river ecosystems include copper (Cu), lead (Pb), zinc (Zn), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), arsenic (As), selenium (Se), iron (Fe), and manganese (Mn). Their concentrations can fluctuate depending on source inputs, streamflow (dilution effects), water chemistry (pH and redox conditions), and interactions between the water in the stream or river and its underlying sediments.Natural sources of dissolved metals include the chemical weathering of rocks and soils. The specific geological characteristics of a watershed plays a significant role. Regions underlain by mineralized rock formations can have relatively high background concentrations of certain metals. Inflows from geothermal springs can be another natural source of metals like arsenic and mercury.

However, anthropogenic activities are often the primary cause of elevated and harmful metal concentrations in rivers. Mining operations are a particularly significant source. Acid mine drainage (AMD), formed when water reacts with sulfide minerals exposed during mining, can release high concentrations of toxic metals (e.g., Cu, Zn, Cd, Pb) and acidity into streams, devastating aquatic life. Leachate from mine tailings piles and waste rock can also contribute metals, even long after mining has ceased. Other human sources include industrial wastewater discharges, atmospheric deposition from smelting or fossil fuel combustion (especially for mercury), urban runoff carrying metals from vehicles and infrastructure, and agricultural runoff.

The primary concern regarding dissolved metals is their toxicity to aquatic organisms. Many metals, even at trace concentrations, can impair physiological functions, reduce growth rates, inhibit reproduction, cause developmental abnormalities, and lead to mortality in fish, invertebrates, and algae. Sensitivity varies among species and life stages. Metals can also bioaccumulate, increasing in concentration within organisms over time, and biomagnify, becoming more concentrated at successively higher trophic levels in the food web. This poses risks not only to aquatic predators but also to terrestrial wildlife (e.g., birds, mammals) and humans who consume contaminated fish. Elevated metal concentrations can render water unsuitable for drinking or irrigation.

Physical Parameters

Many physical water quality parameters are important for the function of aquatic ecosystems. Three of the most important include water temperature, dissolved oxygen, and pH.Natural river temperatures fluctuate daily and seasonally, driven by solar radiation, heat exchange with the atmosphere, heat exchange with the streambed, and the temperature of surface water and groundwater inflows. Riparian vegetation plays an important role in controlling water temperatures by providing shade, which reduces direct solar radiation. Stream width, depth, and flow volume also affect how quickly water heats or cools. Groundwater inputs tend exert a moderating influence on daily and seasonal temperature extremes. Water temperature controls metabolic rates, growth, behavior (e.g., migration timing), and reproductive success for fish and invertebrates. Temperature also directly affects the solubility of dissolved oxygen (colder water holds more DO), influences the rates of somw chemical reactions in the water column, and effects the toxicity of certain pollutants.

Human activities frequently alter thermal regimes in rivers. Thermal pollution can occur through the discharge of heated water from wastewater treatment plants or industrial processes. Dams and reservoirs have complex effects on water temperature. Releases from the warm surface layer of stratified reservoirs can increase downstream temperatures in summer, while releases from the cold bottom layer can cause unseasonably cold temperatures downstream. Dams also tend to reduce natural diurnal and seasonal temperature fluctuations. These changes can disrupt life cycles cues for native fish and aquatic macroinvertebrates. Removal of riparian vegetation eliminates shade and increases solar radiation reaching the water surface. This change to riparian areas can lead to higher summer water temperatures, particularly in smaller streams. Reduced streamflow due to water withdrawals or diversions reduces the volume of water in the stream, decreasing thermal inertia and allowing the stream to heat up more quickly. Channel widening resulting from altered flow or sediment regimes increases the surface area exposed to solar radiation.

Dissolved oxygen (DO) measures the concentration of molecular oxygen in water the water column. DO levels are governed by the balance between processes that add oxygen (e.g., aeration from riffles, photosynthesis by aquatic plants/algae) and processes that consume oxygen (i.e., respiration by all aquatic organisms, decomposition of organic matter by bacteria). DO is inversely related to temperature (colder water holds more DO). DO is essential for the survival of most aquatic animals, including fish and macroinvertebrates, which require oxygen for respiration. Different species have different minimum DO requirements. Coldwater fish generally require higher DO levels than warmwater fish. Low DO levels cause physiological stress, reduced growth, avoidance behavior, and, if severe or prolonged, mortality.

Human activities that increase organic matter loading (e.g., sewage discharge, agricultural runoff with manure or plant residues) stimulate bacterial decomposition, which consumes DO. Nutrient enrichment can cause large swings in DO, driving high levels during daytime photosynthesis and depletion at night and during algae decomposition. Increased water temperatures from channel widening or reservoir effects can lead to reduced DO saturation and increased metabolic rates (and thus oxygen demand) for many animals. Reduced flow rates or channel simplification that reduces the flow of turbulent water over riffles can reduce aeration rates. Releases from the bottom of stratified reservoirs can discharge water with very low DO directly into downstream reaches.

Riparian Vegetation

Riparian zones are unique and vital ecosystems forming the interface between terrestrial uplands and aquatic environments such as rivers, streams, and lakes. Healthy riparian vegetation is characterized by a high level of vertical complexity, including the presence of tree, shrub, and herbaceous vegetation layers. Vegetation also tends to be patchy in terms of species composition, cover, structure and level of development. The rich and patchy characteristics of vegetation in riparian zones is a product of shallow groundwater tables and the regular hydraulic disturbances caused by seasonal flooding.Riparian vegetation influences a wide array of river functions, from channel stability to the filtration of nutrients. The root networks of riparian trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants bind soil particles together, significantly increasing the shear strength and stability of streambanks. The riparian tree and shrub canopy provides shade, intercepting solar radiation and preventing excessive warming of stream water, particularly during summer months. Vegetation slows runoff, allowing sediments and associated particulate pollutants to settle out. Plant roots and soil microbes actively take up dissolved nutrients (like nitrogen and phosphorus) and can degrade certain pesticides and other organic chemicals, preventing them from reaching the water body. Riparian vegetation is the primary source of organic matter (leaves, needles, twigs, terrestrial insects) that forms the base of the food web in many streams, particularly headwaters. Mature trees also contribute large woody fallen logs and branches to the stream channel. The importance of the structure and complexity of riparian habitat is perhaps most commonly associated with the critical role it plays for terrestrial and avian wildlife. Riparian zones provide essential food, water, shelter, and breeding sites for a wide array of terrestrial and semi-aquatic wildlife, including insects, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. They also serve as important movement corridors, connecting fragmented habitats across the landscape.

Human activities that directly impact riparian vegetation include forest clearing for urban development, agriculture, or industry (e.g., gravel pits). Other activities can degrade conditions in the riparian forest. For example, insufficient management of invasive plant and insect species can impact the diversity of riparian plant communities. Human-caused wildfire can devastate riparian forests, particularly in arid and semi-arid potions of the state. Heavy recreational usage can lead to widespread trail development and trampling of herbaceous and shrub communities. Finally, livestock grazing can denude existing plants and suppress recruitment rates for new plants.

Floodplain Connection

Lateral connections between the river and adjacent floodplains significantly influence the health and function of the riparian ecosystem. These hydrological connections facilitate the exchange of water, sediment, nutrients, organic matter, and organisms between the river channel and the riparian zone. Periodic inundation provides fish and amphibians with essential temporary habitats for spawning and rearing. Backwaters and sloughs may be rich sources of food and provide refuge from high water velocities in the main channel. Floodplain inundation drives nutrient cycling, deposits sediments that contribute to building floodplain soils, and provides groundwater recharge.Levees and other features constructed specifically to prevent overbank flow and disconnect the river from its floodplain eliminate lateral connectivity and associated ecological functions. Straightening and deepening channels can increase their capacity and reduce the frequency of overbank flooding, thus impairing lateral connectivity. Reservoirs decrease the frequency, magnitude, and duration of floodplain inundation by reducing or eliminating flood peaks, effectively reducing lateral connectivity even where levees are absent.

Riparian Habitat Connectivity

Riparian zones act as critical corridors for the movement of terrestrial wildlife along river systems, connecting fragmented habitats across the broader landscape. They provide essential resources (food, water, cover) and facilitate dispersal, migration, and gene flow for numerous species, including mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Intact riparian corridors enhance landscape permeability. Connectivity is maintained by continuous stretches of suitable riparian habitat along the river corridor.The ability to move freely through the riparian corridor is of fundamental importance to wildlife species. Regardless of the condition of a riparian habitat patch, if it is inaccessible, its value to wildlife is greatly diminished. Habitat connectivity in healthy riparian ecosystems allows unrestricted movement of wildlife laterally between habitat patches and up and down the corridor to other reaches.

Habitat fragmentation from roads, development, and agriculture physically disconnect riparian patches, creating barriers to wildlife movement. Roads that parallel rivers are particularly problematic, causing direct mortality (roadkill) and acting as barriers to dispersal for many species. Clearing or degrading riparian vegetation reduces habitat quality and cover, making corridors less suitable or unusable for wildlife movement. Fencing can also directly block movement for larger animals.

Floodplain Morphology

Floodplain morphology refers to the shape of the land’s surface. Natural floodplains have complex surface topography caused by flood flows, channel migration and avulsions. Floodplains can contain natural levees, backwaters, terraces, relic channels and swales. Natural levees are slightly elevated ridges immediately adjacent to the channel, formed by deposition of coarser sediment during overbank flows. Backwaters include the low-lying areas further from the channel, that periodically hold water and accumulate finer sediments. Terraces are abandoned, older floodplain surfaces sitting at higher elevations, rarely inundated under the current flow regime. Relict channels and other depressions can hold standing water. Gently undulating ridges and swales reflect historical point bar deposition and lateral channel migration processes.Floodplain topography dictates the pattern, depth, and duration of inundation during floods, creating a mosaic of hydrological conditions. This hydro-topographic complexity supports diverse plant communities adapted to different flood frequencies and soil moisture regimes. It creates a variety of habitats for fish (spawning, nursery areas in backwaters), amphibians, birds, and mammals. Low-lying areas retain floodwaters longer, supporting wetland habitats and influencing nutrient processing and carbon storage. Heterogeneity enhances overall biodiversity and ecosystem resilience.

Land leveling and filling due to agriculture or urbanization simplifies floodplain topography, removing natural depressions, channels, and levees. These changes end up reducing habitat diversity by altering inundation patterns. Construction of gravel mines significantly impacts floodplain topography, often leaving deep ponds over large extents of historical riparian corridor.

Planform Dynamics

Lateral migration is a primary mechanism for floodplain turnover and renewal. Bank erosion supplies sediment (including gravels) and large wood to the channel, essential components for habitat structure. Point bar deposition creates bare, moist surfaces ideal for the establishment of pioneer riparian vegetation like cottonwoods and willows. The process maintains a mosaic of different-aged floodplain surfaces and vegetation communities, increasing overall habitat diversity. Abandoned meander bends can form oxbow lakes, providing important off-channel aquatic habitat. This dynamism prevents channel stagnation and promotes ecosystem resilience.Channel avulsion is a relatively abrupt and often large-scale shift in the course of a river channel, where the river abandons its existing channel to establish a new path across its floodplain. Avulsions are a fundamental process in building alluvial landscapes like floodplains and alluvial fans. They typically occur when the existing channel aggrades to the point where it sits higher than the adjacent floodplain, creating a slope advantage for flow to find a new, lower path. Avulsions often occur during a large flood events that breach a levee or bank. Avulsions are major disturbance events that dramatically reorganize the river corridor landscape. They create new channels, abandon old ones (which may become wetlands or oxbow lakes), redistribute sediment across large areas of the floodplain, and initiate new cycles of riparian vegetation succession. This large-scale resetting process is crucial for maintaining long-term floodplain heterogeneity and ecosystem complexity, particularly in depositional environments like broad alluvial valleys and alluvial fans.

Bank stabilization (e.g., riprap, etc.) directly prevents bank erosion and halts lateral migration. This eliminates sediment and wood input from bank sources, prevents floodplain renewal, and can transfer erosional energy downstream, potentially causing instability elsewhere. Channelization and river straightening eliminates meander bends, thereby stopping lateral migration processes associated with bend dynamics. Flow regulation decreases the frequency and magnitude of flows capable of causing significant bank erosion and channel movement, slowing or halting natural migration rates. Levees confine the river, preventing it from accessing its floodplain and migrating freely across the valley bottom. Riparian vegetation removal can increase bank erodibility and potentially accelerate migration rates. Loss of mature trees reduces long-term streambank stability and wood recruitment. Levees and embankments constructed specifically to prevent avulsions and confine rivers to their current course halt this critical landscape-building process. Dams can reduce downstream sediment loads, decreasing aggradation rates in the main channel, which can reduce the natural processes that trigger avulsions. Increased sediment supply from watershed disturbance can accelerate channel aggradation, potentially increasing avulsion frequency or magnitude if the river is not confined.

Profile Dynamics

Channel bars and riffles are accumulations of sediment deposited within or along the margins of the river channel where local flow velocity and transport capacity decrease. Mid-channel bars form within the channel, often initiated by deposition around obstructions like boulders or large pieces of wood where flow diverges and loses transport power. Bars create topographic and hydraulic diversity within the channel. Exposed bar surfaces provide habitat for terrestrial invertebrates and nesting sites for some birds (e.g., Piping Plover, Least Tern). Bar margins and submerged portions provide shallow water habitat for fish and invertebrates. Bars influence flow patterns, contributing to the formation of adjacent pools and riffles. They are key sites for riparian vegetation colonization, particularly pioneer species. The constant shifting of bars in dynamic systems maintains early successional habitats.Riffles are shallow, high-gradient sections of a channel characterized by coarser substrate and turbulent flow, typically alternating with deeper, lower-gradient pools. Over time, as channels migrate laterally or sediment pulses move through the system, riffles and their crests can gradually migrate downstream. Sediment transport patterns in riffles are complex: at high flows, pools scour and riffles may aggrade, while at lower flows, riffles can be sources of sediment that deposits in pools.Pool-riffle sequences create significant habitat heterogeneity, providing distinct environments for different species and life stages. Riffles offer well-oxygenated, shallow, fast-flowing habitat with coarse substrate, ideal for many macroinvertebrates (especially EPT taxa) and fish spawning. Pools provide deeper, slower water refuge during low flows or temperature extremes. The dynamic migration of these features contributes to the overall shifting habitat mosaic.

Flow regulation decreases the flows needed to mobilize sediment and rework bars, leading to stabilization and vegetation encroachment on formerly active bar surfaces. This can reduce the overall area and dynamism of bar habitats. Flow alteration also changes the magnitude and frequency of high flows required to maintain pool-riffle morphology. Reduced sediment supply below dams can lead to the erosion and loss of downstream bars. Sediment starvation below dams can lead to coarsening or armoring of riffles and potential incision, altering the pool-riffle structure. Conversely, excess sediment supply from land use activities or wildfires can lead to rapid bar growth and channel aggradation. Excess fine sediment can fill pools and embed riffle substrates, degrading habitat quality. Instream structures like weirs can artificially create pool-like features but disrupt natural riffle formation and riffle-crest migration processes.

Reach Complexity

Reach complexity reflects the diversity and distribution of water depth, velocity, and physical cover. Flow velocity, water depth, and boundary shear stress vary spatially across the channel cross-section, longitudinally through various channel units (e.g., faster in riffles, slower in pools), and temporally with changes in discharge. Hydraulic conditions are primary determinants of habitat suitability for aquatic organisms. Different species and life stages have specific requirements or preferences for velocity, depth, and shear stress. For example, some macroinvertebrates require high velocities (e.g., filter feeders in riffles), while others prefer slow-moving pools. Fish select habitats based on velocity (for feeding and energy expenditure), depth (for cover and volume), and shear stress (related to bed stability and suitability for activiites like spawning). Hydraulic forces also govern sediment transport, bedform development, and scour/deposition patterns.Flow alteration directly changes discharge, which in turn alters velocity, depth, and shear stress patterns throughout the channel. Reduced flows decrease velocities and depths, while regulated or hydropeaking flows create unnatural hydraulic fluctuations. Channel straightening increases channel slope and confines flow, leading to higher average velocities and shear stresses, often simplifying hydraulic diversity. Instream structures like weirs, bridges, and culverts create localized hydraulic changes, such as increased velocity through constrictions, flow separation, and altered turbulence patterns.Removal of roughness elements like large wood and boulders reduces hydraulic complexity, leading to more uniform flow conditions.

Streambed Composition

The composition of sediments in the streambed controls the physical quality of habitat used by macroinvertebrates and fish larvae. Quality of these habitats is generally related to the availability of interstitial space within the riverbed, which is driven by how deeply coarse bed material are embedded in fine sediment, the presence of armoring, and widespread algae growth.

Aquatic Habitat Connectivity

Longitudinal habitat connectivity is essential for the natural downstream flow of water, the transport of sediment and nutrients that shape downstream habitats and support ecosystems, the downstream drift of aquatic invertebrates, and the upstream and downstream migrations of fish and other mobile aquatic organisms. Many fish species require access to different habitats throughout the river network for spawning, feeding, and refuge during different life stages or seasons. Maintaining genetic exchange between populations throughout the river network also depends on unimpeded movement between different sub-populations.Dams and weirs are the most significant disruptors of longitudinal connectivity. They physically block upstream and downstream movement of fish and other organisms, isolating populations and preventing access to critical habitats. Dams also fragment the continuity of flow, sediment, and nutrient transport. Poorly designed or maintained culverts are widespread barriers, particularly to smaller fish or during certain flow conditions. Issues include excessive water velocity, inadequate water depth (perched outlets), debris blockage, and lack of natural substrate. Fords can also impede passage, especially at low flows. Irrigation or water supply diversions can create physical barriers to upstream and/or downstream passage. Extreme low flows caused by diversions or drought can fragment habitat longitudinally by creating disconnected pools or drying entire reaches.

Aquatic Macroinvertebrates

Aquatic macroinvertebrates are a diverse group of animals without backbones, large enough to be seen without magnification, that inhabit stream and river bottoms. This group includes aquatic insects (larvae and nymphs of mayflies, stoneflies, caddisflies, beetles, true flies, dragonflies, etc.), crustaceans (crayfish, amphipods, isopods), mollusks (snails, clams), worms, and leeches. They occupy crucial intermediate positions in the food web, linking basal resources to fish and other predators.A useful way to understand the ecological roles of macroinvertebrates is to classify them into functional feeding groups based on their mode of food acquisition. Shredders consume coarse particulate organic matter, such as leaves, needles, and wood fragments originating primarily from riparian vegetation. Shredders are critical for the initial breakdown of terrestrial detritus, especially in headwater streams. Examples include many stoneflies, cranefly larvae, and some caddisflies. Collectors feed on fine particulate organic matter. Gathering collectors actively gather organic matter from bottom sediments. Filtering collectors use specialized structures (nets, fans, gills) to filter organic matter suspended in the water column. Collectors are often abundant across all stream sizes but may dominate in larger rivers. Examples include mayfly nymphs, midge larvae, blackfly larvae, and net-spinning caddisflies. Grazers consume periphyton (attached algae) and associated biofilms by scraping or rasping surfaces like rocks and wood. They thrive in areas with sufficient light penetration for algal growth, such as unshaded mid-order streams or shallow riffles. Examples include snails, water pennies (beetle larvae), and some mayfly and caddisfly species. Predators feed on other animals, primarily other macroinvertebrates. They employ diverse strategies to capture prey. Examples include dragonfly and damselfly nymphs, dobsonfly larvae (hellgrammites), certain stoneflies, and predatory beetles.

Because different macroinvertebrate taxa exhibit varying tolerances to pollution (e.g., low oxygen, sedimentation, chemical contaminants) and habitat conditions, the composition of the macroinvertebrate community serves as an excellent indicator of stream health. The presence and abundance of sensitive groups like mayflies (Ephemeroptera), stoneflies (Plecoptera), and caddisflies (Trichoptera) – collectively known as EPT taxa – generally indicate good water quality, while dominance by tolerant groups like certain worms or midges suggests impairment. Their relatively sedentary nature and long life cycles allow them to integrate environmental conditions over time, providing a more comprehensive assessment than instantaneous water chemistry measurements. Therefore, biological assessments using macroinvertebrates are widely employed in monitoring programs.

Fish

Fish communities represent upper trophic levels in most river food webs and play significant roles as both consumers and regulators of ecosystem structure. Fish exhibit a wide range of feeding strategies and occupy multiple trophic levels. Some species are primarily herbivorous, feeding on algae or macrophytes, or detritivorous, consuming dead organic matter. Many fish are secondary consumers, feeding predominantly on aquatic macroinvertebrates. Larger fish species often act as tertiary consumers or apex predators within the aquatic system, feeding on smaller fish or large invertebrates. Feeding on items from multiple trophic levels (e.g., both invertebrates and smaller fish, or algae and insects) is common among fish species, adding complexity to food web interactions.Fish exert significant influence on the structure and dynamics of river food webs through: Predation by fish can regulate the abundance and composition of macroinvertebrate populations. Intense predation can lead to trophic cascades, where effects ripple down to lower levels, potentially influencing algal biomass by controlling grazer populations. Fish species compete with each other and potentially with other vertebrates (e.g., amphibians) and invertebrates for food resources and habitat space, influencing community structure. Non-native fish species can drastically alter food webs through intense predation on native prey, competition with native fish, or by introducing novel feeding strategies that disrupt established interactions. Because fish integrate environmental conditions over relatively long lifespans and occupy upper trophic levels, the health and composition of the fish community are often considered strong indicators of overall river ecosystem health

Metrics

While the inclusion of Components reduces the level of abstraction inherent in Drivers, they are still too broadly defined to be assessed quantitatively. To accommodate quantitative evaluation of aspects of river process or condition, CoRHAF employs Metrics at a level in the organizational hierarchy below Components. One or more Metrics may be used to assess the condition of a Component. Metrics are are quantifiable aspects of the stream system that provide objective information on Components. Several examples are provided below:

Peak Flow

Metric: Average annual 3-day maximum flow

Base Flow

Metric: Average annual 7-day minimum flow

Metric: Average annual duration of zero flow days

Nutrients

Metric: 85th percentile nitrate concentration

Metric: 85th percentile total phosphorous concentration

Metals

Metric: 85th percentile dissolved zinc concentration

Metric: 85th percentile dissolved copper concentration

Physical Parameters

Metric: July maximum weekly average temperature

Metric: Minimum October dissolved oxygen concentration

Floodplain Connection

Metric: 5-year floodplain inundation extent

Riparian Habitat Connectivity

Metric: Probability of Connectivity Index

Metric: Dispersal success

Riparian Vegetation

Metric: Cottonwood age class structure

Metric: Native tree recruitment rate

Metric: Percent woody cover

Metric: Percent herbaceous cover

Metric: Presence/absence invasive species