Scoping Your Assessment

By now, the purpose of your assessment is clearly articulated. It’s time to put limits on what will be assessed. You must establish the specific geographic, temporal, and analytical scope for the work. This requires thoughtful consideration of stakeholders’ needs and concerns, a feel for the overall character of the watershed or river under consideration, and an initial identification of potential project management or implementation challenges.

Reflect on the Purpose

Your river health assessment’s purpose statement describes why the assessment should occur. Based on the purpose, the group of individuals and/or organizations planning for the assessment should brainstorm a list of primary questions and known problems they want the assessment to address (click here to see some pre-planning questions developed for Stream Management Plans). Group activities can be helpful here. For example, you might hang a large map of the watershed on a wall and ask stakeholders to place sticky notes or dots on areas of concern (e.g., “frequent algal blooms here”), key assets (“important fish spawning area here”), and major inputs to streams or rivers (“stormwater outfall here”). The notes placed on the map can be the basis for articulating questions about specific areas of the watershed or identifying (in a spatially explicit manner) problems that should be evaluated during the assessment.

Delineate Geographic Priorities

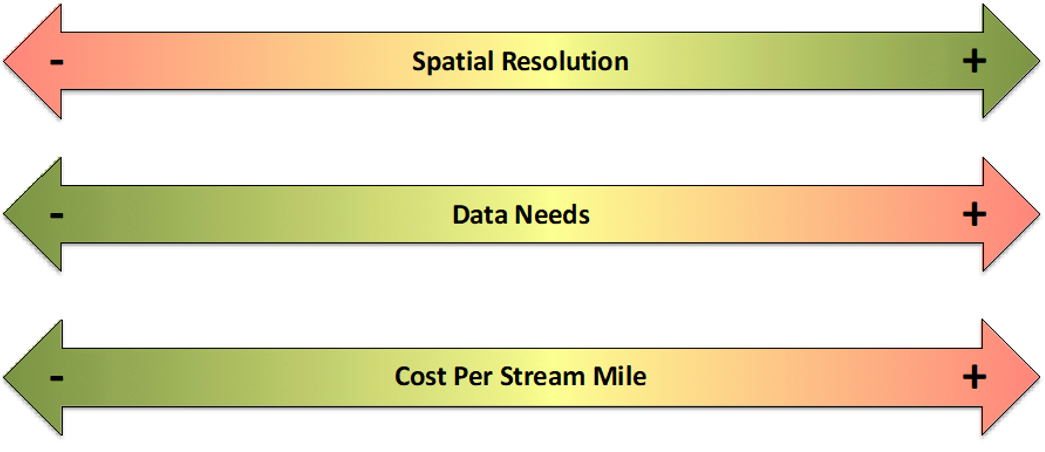

There is no optimal scale for an assessment. In fact, river health assessments may seek to characterize conditions across a wide variety of spatial scales, spanning a range from the channel scale (tens to hundreds of feet) to the reach scale (hundreds of yards to tens of miles) to the watershed scale (many square miles and multiple streams). In determining the “best” scale for your effort, consider the information collected in group activities like the one outlined above or through knowledge of the specific interests of your stakeholder group. This information may form the bounds of the locations or water bodies that are essential to include. It is also prudent to consider any relevant jurisdictional boundaries. For example, if the primary audience for your assessment is a City Council, it may make sense to limit your activities to the scope of City interests. Finally, anticipated budget availability may also constrain your geographic scope. Generally speaking, an effort that covers a greater number of stream miles will be more expensive. If you have limited funding for your assessment, making the geographic extent of your study area equivalently modest will help enable a reliable assessment of your highest priority resources. Where limited budget is available, but the demands of the assessment require a relatively large geographic scope, the assessment approach will need to be centered on low intensity, rapid methods (see section below).

Contemplate Analysis Intensity

The second part of scoping involves getting a handle on the assessment focus. Given limited time and resources, you will need to consider the most critical aspects of your river, those to which most energy should be directed, where you can leverage existing data and information, and where data gaps exist that will need to be filled. This step begins to span the gap between river health and stakeholder concerns. There is no need to address any of these topics in detail during scoping, but this contemplation and articulation will begin to refine expectations for the study and inform budget planning. This is somewhat technical, so you may wish to solicit assistance. Since this step is part of scoping for a future project, consultants or other experts may be willing to help on an informal basis.

Consider Project Timelines

The temporal scope of your assessment includes the overall project duration and timing of project milestones. The timeline is intrinsically linked to the budget, the assessment priorities, and obligations or deadlines associated with grant funding sources. Seasonality is also a critical consideration! Many types of information can only be collected at certain times of year. Meshing this natural constraint with funding awards can be challenging. Creating a temporal scope for your project begins by listing all known project timeline constraints and stakeholder preferences for the timing of interim project deliverables. Use external deadlines, such as grant reporting requirements, governmental decision-making schedules or seasonal limitations to impose firm constraints on overall project duration. Then work backwards to define timelines for any other project milestones or interim project deliverables. It is important to consider your expectations for assessment intensity while building a project timeline. If you expect your river health assessment to cover a large region and to utilize multiple focused quantitative assessments, you will need to allot more time than an effort that is more geographically constrained or reliant on remote assessments.

Utilize Evaluative Criteria

Selection of the ideal geographic scope and assessment intensity for your river health assessment can be an iterative process that attempts to grapple with tension between the desire to assess conditions across large areas at a high level of detail and the reality of limited time and budgets. Arriving at a final scope may require evaluation of multiple distinct and plausible assessment scenarios that reflect different geographic, analytical, and temporal characteristics (e.g., “Scenario A is a comprehensive, multi-year baseline study but is expensive; Scenario B is a lower-cost, single-season study focused on a priority sub-watershed”). Project planners can evaluate each scenario’s cost, complexity, and timeline implications against a set of agreed-upon criteria. These criteria might include:

Relevance: How well does this scenario respond to project’s purpose statement?

Comprehensiveness: Does it include the primary sources of impact and key geographic areas?

Feasibility: Is this scenario realistically achievable within our likely budget and timeline?

Actionability: Will the results from this scope lead directly to tangible management actions or policy decisions?

Data Availability: Does the scenario effectively leverage existing data or does it rely on extensive new data collection?

The outcome of such an evaluation may be the adoption of a single scenario as the preferred project scope. Equally plausible is the combination of desirable elements from different scenarios. For example, the group might choose the geographic scope of Scenario B but incorporate the more detailed analytical intensity for a specific Driver or Component from Scenario A, while adjusting the timeline to seek additional funding sources to support an expanded budget. This iterative refinement can help you identify a scope that is responsive to the stated purpose, reflective of budget realities, and is highly likely to produce outputs for the stakeholders and focus audience that are both timely and relevant.